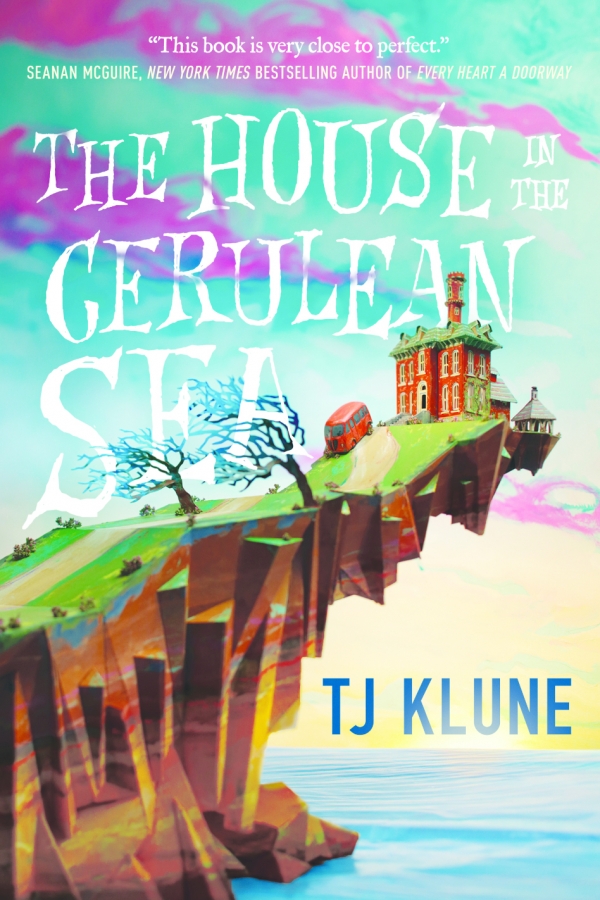

“The House in the Cerulean Sea” is an LGBT fantasy novel by Travis John Klune that explores the idea of finding one’s place in a tough and unforgiving world. The story follows a caseworker at the Department in Charge of Magical Youth (DICOMY), Linus Baker. His job as a caseworker is to investigate and file reports on orphanages registered under DICOMY’s supervision. The only peculiar thing about these orphanages is that they host magical creatures who allegedly pose a grave threat to normal peers if enrolled in a public school. The House in the Cerulean Sea is the most peculiar of all as it hosts potentially apocalyptic magical creatures which, in hindsight, forms a sharp juxtaposition with the beautiful imagery provoked by the description of the House.

Linus is characterized as a highly orthodox and utterly mediocre protagonist who abides strictly and fanatically by the protocols. One day, however, he is assigned a secretive, month-long investigation to an orphanage by the Cerulean Sea. The instruction from DICOMY reads: “This orphanage is different from all the others you’ve been to, Mr. Baker. It is important that you do your best to protect yourself.” Contrary to how the House is portrayed to the outside world and DICOMY, he discovers stunning facts about how the House is managed and the beautiful chemistry between the innocent, allegedly potentially-apocalyptic children. The longer he stays, the more he feels akin to the place. Also, the longer he stays, the more he falls madly in love with the master of the House, Arthur Parnassus.

The novel makes a bold statement about xenophobia – not necessarily limited to a nationalistic sense but also gender, appearance, and personality in general. As the story is told from a third-person narrative limited to the perspective of Mr. Baker, the readers’ state of mind and emotion are highly attached to that of his. Readers go through the same feelings of agitation and fear as he enters the House and encounters the potentially-apocalyptic children for the first time. Readers go through the same feelings of ease and cathartic relief as he slowly discovers the subtle, imbued love that permeates the extraordinary House. This low-key but prominent shift in both Mr. Baker's and the readers’ perspectives of the kids exposes the fault in our prejudices. At some point, Mr. Parnassus takes all the kids out on a small field trip in the neighboring town, and the sheer terror in the townspeople, when they see the kids walking down the street, is horrendous. Those kids have become subjects of fear not because of their wrongdoing but because they are marginalized for their mere existence. Yet, those kids are just as innocent, humanly and, most important of all, child-like as any other child, and they deserve as much love and care. They are the real victims of the system.

In the most unexpected circumstance, Linus found the place he belongs and the person he loves. By the end of the month, the kids and Mr. Parnassus begged Linus to stay and that the House is now his home. When Linus returns to the city after the investigation, he feels as if all the scenery has turned black and white: gloomy weather, metallic high-rises, and cold people. On his first day back in the office with not even a single colleague welcoming him back, he sees his desk completely unperturbed just as he left it and a small ad on the calendar that he remembers seeing a month ago – an ad which had a photo of a shirtless man on the shore of the cerulean sea and the phrase: “Do you wish you were here?”